Dengue Fever Cases Prepared Yuma County Health Officials For Zika Virus

If Yuma County is prepared for the Zika virus, it’s due in part to county officials’ experience with another mosquito-borne illness in 2014. With the first travel-related case of Zika confirmed in the county, how does that experience help them now?

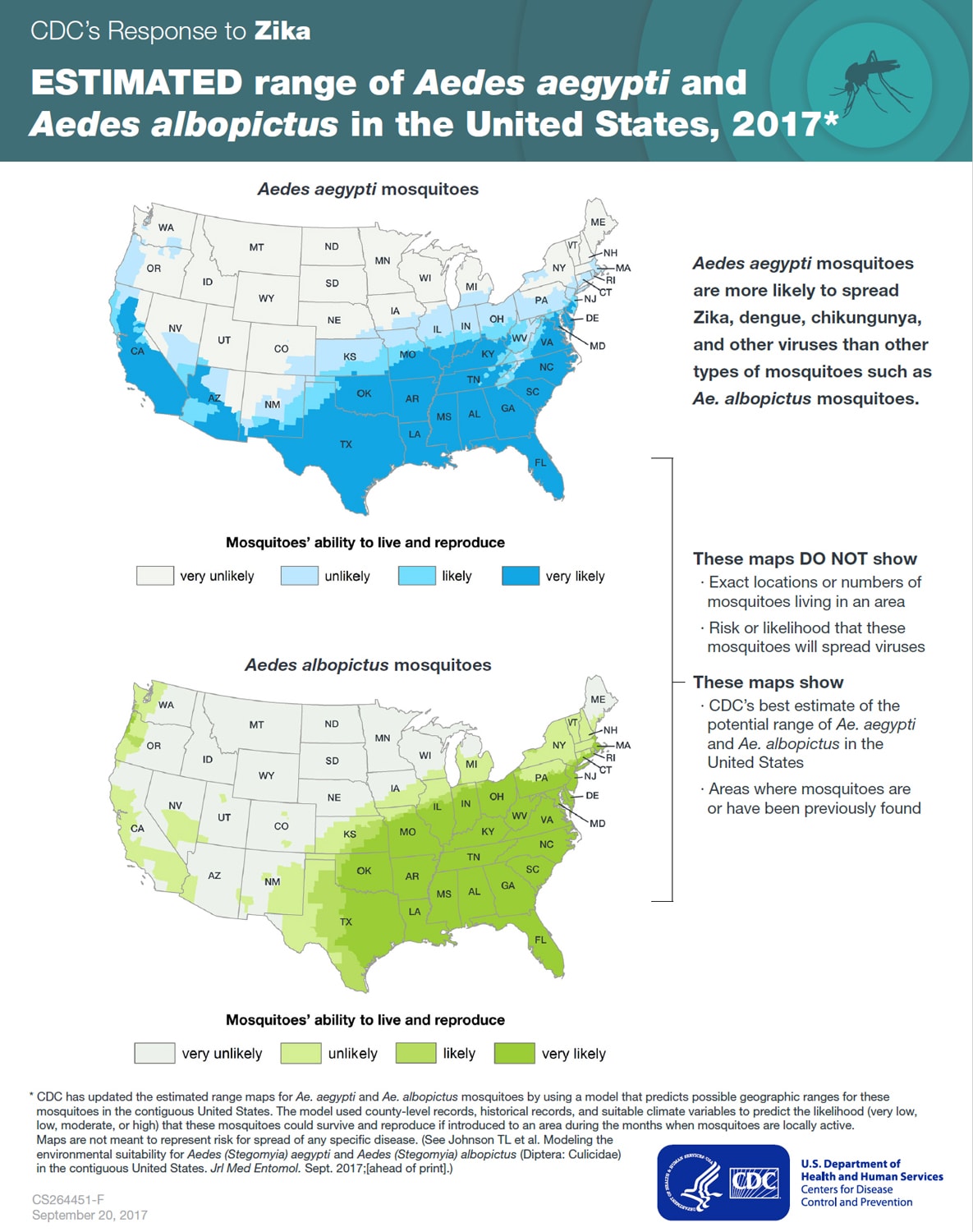

Out at Mittry Lake near Yuma, the warm, humid environment seems perfect for any mosquito. But if you’re looking for the Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that can carry the Zika virus, you’re not likely to find it there. Aedes aegypti prefers an indoor environment. The mosquito can lay eggs in just an inch of water — from office plants to standing dishwater.

The first travel-related case of Zika was discovered in Yuma County in August. That triggered the county to regularly send mosquitoes to the state lab in Phoenix to ensure the local mosquito population was free of Zika. The county has experience with the Aedes aegypti. In May of 2014, Yuma County saw at least 60 travel-related cases of dengue fever, an illness in the same viral family as Zika.

Benito Lopez, the Yuma County epidemiologist, said the county handled those cases with the help of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by educating and tracking patients.

“Well, you’re symptomatic, you have to stay home, [use] mosquito repellent and check in the family if you have any symptoms to try to minimize the exposure to the vectors,” Lopez said.

If a case of dengue or Zika is not locally-acquired, the health department doesn’t have reason to suspect the local mosquito population is infected. Like the Zika cases in Arizona today, Lopez said all the dengue fever cases in 2014 were assumed to be travel-related.

Yuma County Public Health Director Diana Gomez said she believes the county is prepared for Zika because of its response to dengue: strong surveillance and a unique binational partnership with Mexican health officials.

“We saw dengue cases in Mexico," Gomez said. "Then we knew to anticipate them in Yuma County. We were able to talk to our health care providers and say, ‘Listen, you might want to start asking about travel history.’ And that’s how we were able to identify our first cases.”

The CDC says surveillance and education are the best tools to fight Zika. Each county health department should educate infected patients on how to prevent spreading the Zika virus and vector control units track the mosquitoes to fog strategically with pesticides.

Gomez has been sharing this message across the state as the president of the Arizona Local Health Officers Association. The Yuma County Health Department only has two vector control specialists covering the county’s 5,500 square miles, but Gomez said all Arizona health departments have the resources to both educate the public and to arm vector control units with the tools they need.

“We’ve been able to procure funding from the state health department in the form of grants," said Gomez. "The state health department has been incredibly supportive about making sure that all counties, particularly rural counties and those with the highest threat level, are given those resources that they need.”

On the national level, however, emergency funding for the CDC’s response to Zika has not been forthcoming. Yuma County Supervisor Russ Clark, whose board approves county funding for the health department, believes there’s no need to ask for more resources — both at the county and the federal level. He said Congress was right not to approve the $1.9 billion in Zika funding President Barack Obama initially asked for in February.

“We need to do just what we’re doing here in the health department. Watching trends every day, listening to the research. We need to study it and we need to find out and that’s what the CDC is doing today," said Clark. "A trillion and a half dollars isn’t going to make them study faster.”

Zika is linked to brain deformities in babies and only presents flu-like symptoms in 20 percent of those infected. It can spread through blood and saliva and can be sexually transmitted. The virus may live in semen for up to six months.

Earlier this month, a Washington University in St. Louis study suggested Zika might also be transmissible through tears or eye infections.

The CDC is now deploying rapid response teams where cases arise. To date, there have been more than 3,000 travel-related and localized cases of Zika in the continental United States and more than 17,000 in U.S. territories.

Listen to JazzPHX

Listen to JazzPHX